Get the Genesis

of Eden AV-CD by secure

internet order >> CLICK_HERE

Get the Genesis

of Eden AV-CD by secure

internet order >> CLICK_HERE

Windows / Mac Compatible. Includes live video seminars, enchanting renewal songs and a thousand page illustrated codex.

Get the Genesis

of Eden AV-CD by secure

internet order >> CLICK_HERE

Get the Genesis

of Eden AV-CD by secure

internet order >> CLICK_HERE

Windows / Mac Compatible. Includes

live video seminars, enchanting renewal songs and a thousand page

illustrated codex.

Return to Genesis of Eden?

Return to Genesis of Eden?

Governor-General Dame Slivia Cartwright commissoners (from left)

Dr Jacqueline Allan, Sir Thomas Elcholbaum, Dr Joan Fleming and

Right Reverend Richard Randerson, July 27.

GE or not to be

What the government must decide and the future for New Zealand's clean/green image. NZ Listener Oct 27 2001

New Zealand now stands at the crossroads of genetic engineering: proceed with caution or stop right here until we know more about this powerful technology? And do we know enough about the economic implications of the decision to be confident? BY MARK REVINGTON

On the surface, the facts appear simple. A HortResearch scientist wants to field test a strain of tamarillo plants genetically engineered to resist the mosaic virus. He gets permission from the relevant authorities and, in 1998, goes ahead with plantings at the Kerikeri Research Station. Early this year, the tamarillo trees are taken out and HortResearch says the trial is a resounding success. Dig just a little further and there in the large volumes produced by the Royal Commission on Genetic Modification is a reference to the notorious Northland tamarillo trial. "We heard from Dr Daniel Cohen of HortResearch that he was carrying out a field trial of transgenic tamarillos at HortResearch's Northland Research Station. We heard considerable public doubt about the adequacy of the containment of this trial. The commission considers that this public concern was justified. "In light of concerns that have arisen this year in connection with horizontal gene transfer [HGT], we consider that rigorous monitoring of field trials is essential and that all material associated with the trial must be removable from the site." Last week, after much negotiation, HortResearch and GE-free Northland announced a deal to fumigate the 2000 sq m site, the first fumigation of a GE site in New Zealand. HortResearch head of science John Shaw shrugged it off as no big deal. Put the fumigation down to a way of mollifying local concern, rather than any worries about possible environmental contamination. HortResearch, although it agreed to the fumigation, doesn't appear to share the commission's concerns. "The commission didn't hear the evidence and then cross-examine. We have a clean bill of health from En-na [Environmental Risk Management Authority] and MAF on this issue," says chief executive Ian Warrington.

"We're sensitive to the perception that some people have, particularly around Kerikeri, although we don't think it bears much resemblance to scientific reality," says Shaw. "Clearly, the only way to reassure the local community, and the rest of New Zealand, is to carry out fumigation." Confused? Scientists agree that horizontal gene transfer does occur. They cannot agree on its implications. The Royal Commission heard of clear evidence that genes transferred to plants could then transfer to soil bacteria and then onto other plants. Dr Cohen agreed, with a proviso. "What is disputed is the extrapolation of data from laboratory experiments under tightly controlled, highly selective conditions to making claims that, under field conditions, major environmental and public health problems will occur." But not all opponents make such extravagant claims. The problem, according to Neil Macgregor, a biological scientist from Massey University, is that we simply do not know what the risk is. Information about the effects of genetically engineered plants and animals below ground is still mm and extremely fragmented.

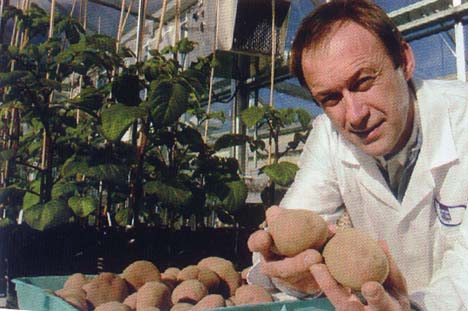

If the scientists can't agree, what chance do the rest of us have? Genetic engineering, it's like this: with GE, we can make a truckload of money and save the Earth. Without GE, we can make a truckload of money and save the Earth. If it seems a little confusing, imagine how the Royal Commissioners felt after 15 public meetings, 28 workshops, 12 hui, a youth forum, a public survey, more than 10,000 written submissions (92 percent of them against genetic engineering), formal hearings lasting 13 weeks, 300 witnesses and almost 100 Interested Persons, all at a cost of $6 million. They slaughtered the beast, studied the entrails, and made 49 recommendations on how to move forward into the biotech century. Asked to evaluate strategic options, the commission settled on a theme of preserving opportunity, Dr Tony Conner of Crop and Food Reasearch at Lincoln with GE Red Rascal potatoes.

Keeping our options open.

On one hand, they rejected a GE-free New Zealand. On the other, they discarded open slather. That left the middle ground. We should move cautiously forward, clutching genetic modification tightly to our bosom, like a particularly thorny bunch of rosebuds that we just know will bloom into stunning maturity. At this stage, especially when it comes to crops and food, genetic engineering promises far more than it has delivered. Just imagine slipping a little DNA here to make grass grow faster, and altering a little DNA there to make strawberries taste better, and identifying various strands over here to get the best wood density to make paper. The reality so far on the land is tamarillos that don't get the mosaic virus, and insect- resistant corn. We're waiting for those buds to open, with all their promise. Which way will we go? The government is expected to announce its intention after a Cabinet meeting on October 27. Lobbying has reached melting-point. Pro-GE groups are preaching doom and gloom if the moratorium is rolled over. Dairy giant Fonterra threatened to take its research offshore and warned that the concept of a "knowledge society" must include biotechnology in all its forms. Spokesman Matthew Hooton said the company had no plans at present to use genetic engineering but wanted to keep its options open. The public are bombarded with cartoon images. One day it's the frill-page newspaper ad funded by Agcarm, a group of biotech companies, "in the interests of creating a better, more prosperous New Zealand". It depicts two bananas in the shape of the country, and the line, "Without controlled research and development on GE technology, here's what New Zealand could grow into." The next day it's retaliation on a slightly smaller scale from the Pure Food Coalition, which tells us "the issue is not 'science' vs 'non-science', it is profit-oriented corporate ('non-ethics') science vs the safety of our food and the integrity of our health". The ad features the image of a cow with a human face and the question: "If GE is so safe, why won't any insurance company insure it?"

GE proponents were delighted by the Royal Commission's findings. No surprise there. Even sweeter was the knowledge that the Greens had instigated the Royal Commission, but it hadn't backed their desire to leave genetic engineering in the lab. Not overtly at any rate, although an optimist could point to certain recommendations that, if enacted, could certainly stop field trials or commercial release, but only on a case-by-case basis. Says Warrington, who also chairs the Association of Crown Research Institutes: "They gave due consideration to a huge volume of evidence from a wide range of parties ... I think they came up with a very useful and very helpful set of recommendations from a very complex exercise." He pauses but cannot resist a dig. "The Greens asked for the Royal Commission. They got it." Green co-leader Jeanette Fitzsimons believes the commission, by focusing on one strategic outcome, failed its warrant. The report recognised the risks of releasing GE organisms into the environment and uncertainty about the technology, says Fitzsimons. Yet, in trying to be all things to all people, it failed to offer leadership. "They wanted to have their cake and eat it," says Green MP Ian Ewen-Street. Theoretical biologist Peter Wills calls it the Royal Omission, a report with recommendations that disregarded the wishes of those who asked for New Zealand's environment to be kept GE-free, even for the time being. "Everything can exist side by side. It doesn't matter that mounting evidence suggests that humans are pretty well incapable of keeping GE farming and organic farming properly separate from each other. New Zealanders will work out, as no one else has managed to, how to make cross-contamination impossible." The commission's report is not the robust document some would like to believe, says Macgregor. But it is the start of an absolutely essential public process. "The transgenic world is here but, surprisingly, we know very little about how it all fits together. Yet we hear strident and indefatigable messages that everything is okay, everything is so intrinsically unimportant that we shouldn't worry about it. "We are in the early stages of getting information. There are things being done in laboratories that would just make your eyes blink. But the kind of science that attends that has far outstripped the kind of science that is now required to make environmental measures and detections of where genes may go in this brave new world." Macgregor highlights the commission's recommendation 6.12, which requires research on the environmental impacts on soil and ecosystems before release of genetically modified crops is approved, and recommendation 7.4, which says that, "in connection with any proposal to develop genetically modified forest trees, an ecological assessment be required to determine the effects of the modification on the soil and environmental ecology, including effects on soil micro-organisms, weediness, insect and animal life, and biodiversity". "That is one [6.121 where there has currently been an omission of those kinds of research, although we do have field trials in operation. I don't quite know what the public perception of a field trial is, but it means controlled in a manner that involves living under natural conditions. There are some field trials authorised and under way in which there is no requirement for an environmental impact [report] and the commissioners picked this up. "This is catch-up time and the commission is indicating we have to start right now. Let's get this right. We are not in the early stages of transgenic animals and plants. It has been going on for 10 years at least. The Royal Commission wasn't the start of the genetic-engineering debate here. It has been going on for quite a while, but it's been kept under wraps and the public has not been kept apace of scientific developments."

Just how far into the paddock we take biotechnology is up to the government. The elation of groups such as the Life Sciences Network and Federated Farmers, wore off as they realised the possible political dimensions. "The value of the Royal Commission will clearly be negated if we get a politically expedient decision," says Federated Farmers president Alistair Polson, an enthusiastic supporter of genetic engineering. "That is likely because the Greens are an obvious coalition partner It's fair to say, without naming names, that there is a definite climate for doing a deal with the Greens, although I don't think Labour is united on this." Polson subscribes to the theory that New Zealand will become a sleepy backwater if it remains GE-free. At a meeting of Calms Group farm leaders in Uruguay, many delegates were amazed at New Zealand's approach, says Polson. To them, GE crops were a part of life. Millions of people had been consuming them for years with no danger: "Let's use the best of safe, new technology for the benefit of all production." Polson's emphasis on production highlights an aspect of the debate that critics say wasn't adequately covered by the commission. The first wave of genetically engineered crops was designed with producers in mind, not consumers. But, in Europe particularly, and increasingly in countries such as japan and the US, consumers are questioning the benefits of GE food. What would be the cost to New Zealand if its "clean green" image were tainted by the commercial release of genetically engineered crops? Would organics survive, as the commission says they can, alongside genetically engineered crops, albeit with a buffer zone between them? What do customers in our export markets want, and what do farmers here want? In fact, research carried out by Andrew Cook and John Fairweather of Lincoln University and Hugh Campbell from Otago found that most farmers supported a broad organic sector with a niche gene technology sector. They found that 21 percent of farmers intended to use gene technology, but 37 percent intended to use organic methods.

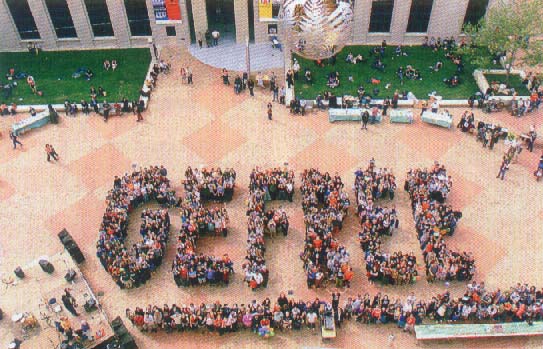

Bic Runga - prominent NZ artists joined to

oppose GE

Bic Runga - prominent NZ artists joined to

oppose GE

Of the farmers and growers surveyed, 49 per- cent agreed and 32 percent disagreed that New Zealand should try to become GE-free. Furthermore, Caroline Saunders and Selim Cagatay of the commerce division at Lincoln University recently published an economic analysis of the issues surround- ing the release of GE food products here. Their conclusion? That the best option for New Zealand would be to delay the commercial release of GE food until the extent of negative consumer attitudes can be seen and the benefits to producers become clearer. That option was also raised during the commission hearings by the Royal Society. Noting the definite shift in consumer preference away from GE food, Saunders and Cagatay suggested that our primary sector would make more money through remaining GE-free and exploiting consumer resistance to genetic engineering in offshore markets, particularly Europe and japan. Has a value been placed on the opportunities afforded by delaying or even resisting the GE revolution? A Ministry of Environment survey found that New Zealand's "clean, green" brand could be worth billions of dollars in the market place. Its methodology has been dismissed by pro-GE groups, notably Life Sciences Network executive director Francis Wevers, who said it was nothing more than a few people standing outside a supermarket asking questions. The Life Sciences Network commissioned its own research that in turn was dismissed in a peer review by economic analysts Berl, which said the conclusion could not be justified. Hugh Campbell, who was one of the peer reviewers of the Ministry of Environment report, admits that it is a preliminary study. "But the major message I got was not what they discovered, but how little work we've done in Us area. We're making sweeping strategic decisions on New Zealand's food exports based on an absolute paucity of data. "Caroline Saunders at Lincoln has done credible research which raises credible questions about whether there will be any economic benefit at all from allowing commercial GE releases. That's one model. There is the Infometrics research which Life Sciences commissioned, and the third is the Ministry of Enviromnent's study, which frankly was extremely preliminary. It speaks to me of the amazing intellectual immaturity of Now Zealand in strategising these options. Everyone jumps on the bandwagon and no one actually says, 'Well, have we got any hard data?' "It feels very much like New Zealand in 1984 all over again and one Treasury -in strategy document comes out saying we've seen the Promised Land and 15 years later we're still waiting for any evidence that it might work. "Saunders's work is actually pointing to where we might ask questions. Economically, to simply look at whether you can make an incremental productivity or efficiency gain on a farm or orchard is highly deceptive, because the critical factor influencing the fate or economic performance is trade. We should be conducting a far more rigorous analysis of where the markets are heading on this." Wendy McGuinness, an accountant specialising in environmental risk management, points out that the commission failed to analyse the economic models presented to it. "The commission only reports excerpts from some witness statements about economic issues and GM, but there is no actual analysis to evidence its conclusions. " In that case, says McGuinness, how could the commission say that it was unrealistic to develop the organic sector at the expense of conventional farming and/or GE? The commission also believed that it was too early to predict consumer reaction with any certainty. The lack of critical evaluation of consumer resistance is a serious weakness, she says. "No businesses would refuse to complete a forecast because it was too early to predict consumer resistance ... In addition I do not understand why it is too early to predict consumer reaction. We have a proven increase in demand for GE- free and organic food, demand for compulsory labelling, and numerous international surveys, all indicating consumer reaction. Consumers in Europe and Asia have also demonstrated a strong anti-GE stance." just ask the American Corn Growers Association. Its members are disillusioned, tired of watching their offshore markets fade away, and tired of prices dropping due to consumer resistance. A survey showed that 77 percent thought that consumer and foreign market concerns about genetically modified organisms were very or some- what important, and 78 percent said they were willing to plant traditional non-GMO corn varieties instead of biotech GMO varieties to keep world markets open to US COrn. "Our analysis revealed that 73.7 percent of the farmers in the survey believe that customer rejection of GMOs contributes to the ongoing low commodity prices received by com growers and 56 percent believe Congress should require the labelling of foods and export cargoes to show GMO levels," says chief executive Larry Mitchell. "The ACGA believes an explanation is owed to the thousands of American farmers who were told to trust this technology, yet now see their prices fall to historically low levels while other countries exploit US vulnerability and pick off our customers one by one." The European Union wants to lift an unofficial moratorium on commercial releases of GE crops, while keeping its consumers happy. It may prove difficult. One survey showed that the number of those who thought food production was a useful application of biotechnology dropped from 54 percent in 1997 to 43 percent last year. A large majority (74 percent) approved of EU moves towards strict labelling of GE foods, while 53 percent said they would pay more for non-GE foods and 36 percent would not. David Byrne, European Commissioner for Health and Consumer Protection, spelt it out in a speech in Washington two weeks ago. Life sciences and biotechnology had huge potential, he said. But they must earn the trust of consumers. "There are different public attitudes on both sides of the Atlantic to the issue. The vast bulk of the 44 million hectares of GM food crops grown globally is here in the United States. In Europe, there is hardly any grown. There is an irrational fear of GM food in the EU. On the other hand, there are irrational fears on this side of the Atlantic about how we in Europe are pro- posing to address the issue. Let me be very frank. Unless we can give EU consumers confidence in this new technology, then GM is dead in Europe." The ECU's label regime would give consumers confidence that only products thoroughly tested for safety would be allowed on the market, said Byrne. "Our consumers are demanding this. They are entitled to choice and full information. To those who say that these labels are not science-based, let me say this. Labelling is not an issue for science alone. It is an issue for consumer information. It may not be fully appreciated widely that consumer information is now a right since the Amsterdam Treaty has become part of the constitutional arrangements of the European Union." The issue in a nutshell, not only for Europe, but for New Zealand - arguably at the forefront of official policy setting in the field of genetic engineering and consumer rights. Given the political implications for the Clark government - accommodation with the ascendant Greens, a wide urban middle-class constituency with real misgivings about GE and food quality in general, an educated guess might suggest the following route: the government extends the moratorium on the commercial release of GE products and allows some tightly controlled field trials. It won't mean the end of the world, but it will give us time to better understand the risks.