Get the Genesis

of Eden AV-CD by secure

internet order >> CLICK_HERE

Get the Genesis

of Eden AV-CD by secure

internet order >> CLICK_HERE

Windows / Mac Compatible. Includes live video seminars, enchanting renewal songs and a thousand page illustrated codex.

Get the Genesis

of Eden AV-CD by secure

internet order >> CLICK_HERE

Get the Genesis

of Eden AV-CD by secure

internet order >> CLICK_HERE

Windows / Mac Compatible. Includes

live video seminars, enchanting renewal songs and a thousand page

illustrated codex.

Return to Genesis of Eden?

Return to Genesis of Eden?

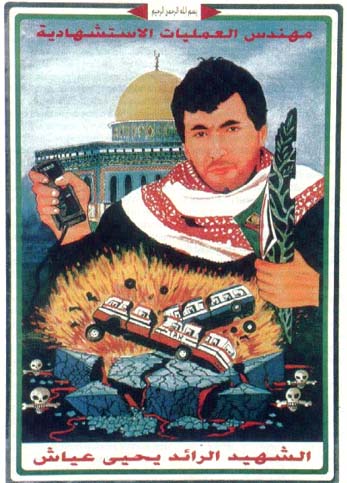

A poster commemorating Yahya, Ayyash, called "the Engineer,"

who developed hamas's strategy of suicide attacks. His assassination,

in 1996, set off a wave of bombings.

LETTER FROM GAZA AN ARSENAL OF BELIEVERS

Talking to the "human bombs."

BY NASRA HASSAN NY 19 nov 2001

Just before midnight on june 30,1993, three members of the Palestinian fundamentalist group Hamas sat in their hideout, a cave in the hills near Hebron, and began reciting from the Koran. At dawn, when the men heard the morning call to prayer from a mosque in the village below, they knelt and uttered the traditional invocation to Allah that Muslim warriors make before setting off for combat. They put on clean clothes, tucked the Koran into their pockets, and began the long hike over the hills and along dry riverbeds to the outskirts ofierusalem. In the Palestinian neighborhoods of East Jerusalem, they walked in silence so that their accents, the guttural vemacidar of Gaza, would not arouse suspicion. Along the way, they stopped to pray at every mosque. At dusk, they boarded a bus that was heading toward West Jerusalem, filled with Israeli passengers. When the driver thwarted their attempt to hijack the vehicle, they tried to detonate the homemade bombs they were carrying. T'he bombs failed to go off, so they pulled out guns and began firing wildly. The shots injured five passengers, including a woman who later died. The young men fled the bus, hijacked a car at a red light, and forced the driver to take them toward Bethlehem. Israeli security forces stopped them at a military checkpoint, and in a shootout two of the young men and their hostage were killed. The dead hijacker, whom I will call S., was struck by a bullet in the head; he lay comatose for two months in Israeli hospitals. Finally, he was pronounced brain-dead, and the Israelis sent him back to his family in the Gaza Strip to die. But S. recovered, and when we met, five years later, he told me his version of the events. By then, he was married antl the father of three sons. Each of them had been named for shaheed bata 'martyr heroes." In Gaza, S. is celebrated as a young man who "gave his life to Allah' and whom Allah "brought back to lie." He was polite as he welcomed me into his home. The house was surrounded by a high cement wall that had been fortified with steel. We sat down in a large, simply furnished room whose walls were inscribed with verses from the Koran. On one wall was a poster that showed green birds flying in a purple sky, a symbol of the Palestinian suicide bombers. S. had recently turned twenty-seven. He is of slight build, and he walked with a Emp, the oray trace of his near-death. He invited his wife to join us, and he answered my questions without hesitation. I asked him when, and why, he had decided to volunteer for martyrdom. "In the spring of 1993, 1 began to pester our military leaders to let me do an operation," he said. "It was around the time of the Oslo accords, and it was quiet, too quiet. I wanted to do an operation that would incite others to do the same. Finally, I was given the green light to leave Gaza for an operation inside Israel." "How did you feel when you heard that you'd been selected for martyrdom?" I asked. "It's as if a very high, impenetrable wall separated you from Paradise or Hell," he said. "Allah has promised one or the other to his creatures. So, by pressing the detonator, you can immediately open the door to Paradise - it is the shortest path to Heaven." S. was one of eleven children in a middle-class family that, in 1948, had been forced to flee from Majdal to a refugee camp in Gaza, during the Arab-Israeli war that started with the creation of the State of Israel. He joined Hamas in his early teens and became a street activist. In 1989, he served two terms'm Israeli prisons for intifada activity, including attacks on Israeh soldiers. One of his brothers is serving a life sentence in Israel. I asked S. to describe his preparations for the suicide mission. "We were in a constant state of worship," he said. "We told each other that if the Israelis knew how joyful we were they would whip us to death! Those were the happiest days of my life."

"What is the attraction of martyrdom?" I asked. "The power of the spirit pulls us upward, while the power of material things pulls us downward," he said. "Someone bent on martyrdom becomes immune to the material pull. Our planner asked, 'What if the operation fails?' We told him, 'In any case, we get to meet the Prophet and his companions, insballah.' We were floating, in the feeling that we were about to enter eternity. We had no doubts.

We made an oath on the Koran, in the presence of Allah - a pledge not to waver. This jihad pledge is called bayt al ridwan, after the garden in Paradise that is reserved for the prophets and the martyrs. I know that there are other ways to do jihad. But this one is sweet-the sweetest. All martyrdom operations, if done for A.UaWs sake, hurt less than a gnat's bite!" S. showed me a video that documented the final planning for the operafion. In the grainy footage, I saw him and two other young men engaging in a ritualisfic dialogue of questions and answers about the glory of martyrdom. S., who was holding a gun, identified himself as a member of al-Qassam, the military wing of Hamas, which is one of two Palestinan Islamist orgzations that sponsor suicide bombings. (Islamic Jihad is the other group.) "Tomorrow, we will be martyrs," he declared, looking straight at the camera. "Only the believers know what this means. I love martyrdom The young men and the planner then knelt and placed their right hands on the Koran. The planner said, "Are you ready? Tomorrow, you will be in Paradise."

Since 1982, I have been an international relief worker, and after 1987 myjob brought me regularly to the Middle East, especially to the Palestinian territories. In 1996, I was posted in the Gaza Strip during one of the most vicious cycles of suicide bombings. To understand why certain young men voluntarily blow themselves up in the name of Islam, I began, without official sponsorship, to research their backgrounds and the beliefs that had led them to such extreme tactics. Finding people who were willing to discuss the details of these activities was no easy task I was warned that my interest in trying to understand the sw'cide missions was dangerous. One day, I stopped to buy fruit at a roadside stand in the south of the Gaza Strip. When I asked where the mangoes had come from, the vender smiled and said, "From Belt Lid, Hadera, and Afula three Israeli towns that had been attacked by suicide bombers. Eventually, when the people who were observing me had assured themselves of my credentials important one was that I am Muslim and from Pakistan - I was allowed to meet with members of Hamas and Islamic jihad who could help me in my research. "We are agreeing to talk to you so that you can explain the Islamic context of these operafions," one man told me. "Even many in the Islamic world do not understand." Our meetings, which were arranged by intermediaries of all kinds, took place late at right, in back rooms, in small local cafes, on the sewage-strewn Gaza beach, or in prison cells. I woiad drive to a rendezvous point to pick up a contact,who then guided me to a meeting by way of a circuitous, untraceable route. From 1996 to 1999, l interviewed nearly two hundred and fifty people involved in the most militant camps of the Palestinian cause: volunteers who, like S., had been unable to complete their suicide missions, the families of dead bombers, and the men who trained them. None of the suicide bombers - they ranged in age from eighteen to thirtyeight conformed to the typical profile of the suicidal personality. None of them were uneducated, desperately poor, simple-minded, or depressed. Many were middle class and, unless they were fugitives, held paying jobs. More than half of them were refugees from what is now Israel. Two were the sons of millionaires. They all seemed to be entirely normal members of their families. They were polite and serious, and in their communities theywere considered to be model youths. Most were bearded. All were deeply refigious. They used Islamic terminology to express their views, but they were well informed about politics in Israel and throughout the Arab world. I was told that in order to be accepted for a suicide mission the volunteers had to be convinced of the religious legitimacy of the acts they were contemplating, as sanctioned by the divinely revealed religion of Islam. Many of these young men had memorized large sections of the Koran and were well versed in the finer points of Islamic law and practice. But their knowledge of Christianity was rooted in the medieval Crusades, and they regarded judaism and Zionism as synonymous. When they spoke, they all tended to use the same phrases: "The West is afraid of Islam." "Allah has promised us ultimate success." "It is in the Koran." "Islamic Palestine will be liberated." And they all exhibited an unequivocal rage toward Israel. Over and over, I heard them say, "The Israelis humiliate us. They occupy our land, and deny our history." Most of the men I interviewed requested strict anonymity; they insisted that not even their iniitials be noted. "With just a small detail like that, the security services could identify me," one said. Some of them were masked and met me in dark rooms or parked cars at night so that I couldn't see their faces. The majority spoke in Arabic, and they all talked matter-of-factly about the bombings, showing an unshakable conviction in the tightness of their cause and their methods. When I asked them if they had any qualms about killing innocent civilians, they would immediately respond, "The Israelis kill our children and our women. This is war, and innocent people get hurt."

They were not inclined to argue, but they were happy to discuss, far into the night, the issues and the purpose of their activities. One condition of the interviews was that, in our discussions, I not refer to their deeds as suicide," which is forbidden in Islam. (Their preferred term is "sacred explosions.") One member of al-Qassam said, "We do not have tanks or rockets, but we have something superior-our exploding Islamic human bombs. In place of a nuclear arsenal, we are proud of our arsenal of believers."

The first suicide bombing by an Islamist Palestinian group took place in the West Bank in April, 1993; the latest was in October, 2001. Between 1993 and 1998, thirty-seven human bombs exploded; twenty-four were identified as the work of Hamas, thirteen as that of Islamic Jihad. Since the eruption of the second intifada, in September, 2000, twenty-six human bombs have exploded. Hamas claims responsibility for nineteen of them; Islamic jihad claims seven. To date, an estimated two hundred and fifteen Israelis have been killed in these explosions, and some eighteen hundred have been injured. The attacks have taken place in shopping malls, on buses, at street comers, in cafes wherever people congregate. Hamas and Islamic jlhad consider suicide bombings a military response to what they regard as Israeli provocations. But there is a clear correlation between the peace process and cycles of suicide attacks designed to block progress. Whenever I broached the issue, however, the Islamists denied that there was any such link. Before September 11th, Islamist filndamentalist groups had sponsored human bombings not only in the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, and Israel but also in Afghanistan, Algeria, Argentina, Chechnya, Croatia, Kashmir, Kenya, Kuwait, Lebanon, Pakistan, Panama, Tajikistan, Tanzania, and Yemen. The targets have ranged from ordinary people to world leaders, including the Pope, who was to have been assassinated in Manila in 1995. Dressed as a priest, the assassin presumably planned to detonate himself as he kissed the Pontiff's ring. In 1988, Dr. Fathi Shiqaqi, a founder of the Palestinian Islamic jihad, whose assassination, in 1995, was attributed to Mossad, Israel's secret service, wrote a document in which he laid out the importance of penetrating enemy territory and set down guidelines for the use of explosives in martyrdom operations. These rules were aimed at countering religious objections to the truck bombings that had become almost routine in Lebanon in the nineteen-eighties. Shiqaqi encouraged what he called "exceptional" martyrdom as a necessary tactic in jihad fisabeel A1lah (striving in the cause of Allah): "We cannot achieve the goal of these operations if our mujahid - holy warrior is not able to create an explosion within seconds and is unable to prevent the enemy from blocking the operation. All these results can be achieved through the explosion, which forces the mujahid not to waver, not to escape; to execute a successful operation for religion and jihad; and to destroy the morale of the enemy and plant terror into the people." This capability, he said, is "a gift from Allah." Y Ayyash, an engineering student in the West Bank who became a master bomb-maker, was the first to propose that human bombs be adopted in Hamas's military operations. (The late Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin dubbed Ayyash "the Engineer," which became his nickriarne in the Palestiiian streets.) In a letter written in the early nineties to the Hamas leadership, he recommended the use of human bombs as the most painful way to inflict damage on the Israeli occupation forces. According to a source in Hamas, Ayyash said, "We paid a high price when we used only slingshots and stones. We need to exert more pressure, make the cost of the occupafion that much more expensive in human lives, that much more unbearable." The assassination of Ayyash, in january, 1996, which is widely believed to have been the work of Israeli secun'ty forces, set off a wave of retaliatory suicide bombings. My contacts told me that, as a military objective, spreading fear among the Israelis was as important as killing them. Anwar an Isamic jlhad member who blew himself up in an ambulance in Gaza, in December, 1993, had often told friends, "Battles for Islam are won not through the gun but by striking fear into the enemy's heart." Another Islamist military leader said, "lf our wives and children are not safe from Israeli tanks and rockets, theirs will not be safe from our human bombs." Military commanders of Hamas and Islamic jlhad remarked that the human bomb was one of the surest ways of hitting a target. A senior Hamas leader said, "The main thing is to guarantee that a large number of the enemy will be affected. With an explosive belt or bag, the bomber has control over vision, location, and timing." As today's weapons of mass destruction go, the human bomb is cheap. A Palestinian security official pointed out that, apart from a willing young man, all that is needed is such items as nails, gunpowder, a battery, a light switch and a short cable, mercury (readily obtainable from thermometers), acetone, and the cost of tailoring a belt wide enough to hold six or eight pockets of explosives. The most expensive item is transportation to a distant Israeli town. The total cost of a typical operation is about a hundred and fifty dollars. The sponsoring organization usually gives between three thousand and five thousand dollars to the bomber's family.

In Palestinian neighborhoods, the suiicide bombers' green birds appear on posters, and in graffiti - the language of the street. Calendars are illustrated with the "martyr of the month." Paintings glorify the dead bombers in Paradise, triumphant beneath a flock of green birds. This symbol is based on a saying of the Prophet Muhammad that the soul of a martyr is carried to Allah in the bosom of the green birds of Paradise. Children who cannot read chant the names of the heroes, and make the Islamist sign for victory right fist with raised forefinger-as they play in narrow alleys. A biography of a martyr named Muawiyya Ruga, who exploded a rigged donkey cart near a Jewish settlement in the Gaza Strip in June, 1995, tells of how his soul was borne upward on a fragment of the bomb. In April, 1999, I met with an Imam affiliated with Hamas, a youthful, bearded graduate of the prestigious al Azhar University, in Cairo. He explained that the first drop of blood shed by a martyr durlng jihad washes away his sins instantaneously. On the Day of Judgment, he will face no reckoning. On the Day of Resurrection, he can intercede for seventy of his nearest and dearest to enter Heaven; and he will have at his disposal seventy-two houris, the beautiful virgins of Paradise. The Imam took pains to explain that the promised bliss is not sensual. Sheikh Ahmed Yassin is the spiritual leader of Hamas. He was released from an Israeli prison in 1997, and during the next two years I had many meetings with him, in his small house on an unpaved lane in a crowded quarter of Gaza. He cautioned that I would find it hard to make martyrdom comprehensible to Western readers. "I doubt that they will be willing to understand your explanations," he said. "Love of martyrdom is something deep inside the heart. But these rewards are not in themselves the goal of the martyr. The only aim is to win Allah's satisfaction. That can be done in the simplest and speediest manner by dying in the cause of Allah. And it is Allah who selects the martyrs." There is no shortage of willing recnuts for martyrdom. "Our biggest problem is the hordes of young men who beat on our doors, clamoring to be sent," a Hamas leader told me. "It is difficult to select only a few. Those whom we turn away return again and again, pestering us, pleading to be accepted." A senior member of al-Qassam said, "The selection process is complicated by the fact that so many wish to embark on this journey of honor. When one is selected, countless others are disappointed. They must learn patience and wait until Allah calls them." He told me that there had been many attempts on his life, and he made sure that we always met at a clifferent time and in a different place. He wore a scarf over his face; only at our last meeting, when he was saying goodbye, did he remove it. "After every massacre, every massive violation of our rights and defilement of our holy places, it is easy for us to sweep the streets for boys who want to do a martyrdom operation," he said. "Fending off the crowds who demand revenge and retaliation and insist on a human bombing operation - that becomes our biggest problem!" Hamas and Islamic Jlhad recruit youths for potential leadership positions in the organizations, but their military wings rely on volunteers for martyrdom operations. They generally reject those who are under eighteen, who are the sole wage earners in their families, or who are married and have family responsibilities. If two brothers ask to join, one is turned away. The planner keeps a close eye on the volunteer's self-discipline, noting whether he can be discreet among friends and observing his piety in the mosque. (A cleric will sometimes recommend a notably zealous youth for martyrdom.) During the week before the operation, two "assistants" are delegated to stay with the potential martyr at all times. They report any signs of doubt, and if the young man seems to waver, a senior trainer will arrive to bolster his resolve. The father of Anwar Sukkar, who, with his friend Salah Shakir, carried out an explosion in Beit Lid in 1995, told me with pride, "Even after Salah saw my son ripped to shreds, he did not flinch. He waited before exploding himself, in order to cause additional deaths." A planner for Islamic iihad said that his organization carefully scrutinizes the motives of a potential bomber: "We ask this young man, and we ask ourselves, why he wishes so badly to become a human bomb. What are his real motives? Our questions are aimed at clarifying first and foremost for the boy himself his real reasons and the strength of his commitment. Even if he is a longtime member of our group and has always wanted to become a martyr, he needs to be very clear that in such an operation there is no drawing back. Preparation bolsters his conviction, which supports his certitude. It removes fear." A member of Hamas explained the preparation: "We focus his attention on Paradise, on being in the presence of Allah, on meeting the Prophet Muhammad, on interceding for his loved ones so that they, too, can be saved from the agonies of Hell, on the houri's, and on fighting the Israehli occupation and removing it from the Islamic trust that is Palestine." (A volunteer whom the Palestinian Authority arrested before he could carry out a sw'cide bombing offered this description of the immediacy of Paradise: "It is very, very near----right in front of our eyes. It lies beneath the thumb. On the other side of the detonator.") One of the "technical considerations" that may be taken into account in the final selection of a candidate for martyrdom is the ability to pass, at least temporarily, asan lsraeli Jew In lslamic jihad's first human-bomb operation, in September, 1993, the martyr AloCa al Kahlout shaved his beard, donned a cap and dark glasses, and dressed in shorts and a T-shirt before carrying his bomb onto a bus in Ashdod. I asked one planner about the problem of fear. "The boy has left that stage far behind," he said. "The fear is not for his own safety or for his impending death. It does not come from lack of confidence in his ability to press the trigger. It is awe, produced by the situation. He has never done this before and, insballab, wiu never do it again! It comes from his fervent desire for success, which will propel him into the presence of Allah. It is anxiety over the possibility of something going wrong and denying him his heart's wish. The outcome, remember, hes in Allah's hands." I was told the story of a young Palestinian, M., by two men who, at different times, had been his cellmates in Israeb prisons. In September, 1993, in a safe house just outside Jerusalem, M. had performed ritual ablution, said his prayers, and set off on his bombing mission. He had boarded a bus - one on the same route on which S.'s bomb had failed to explode two months earlier. All he had to do was unzip his bag of explosives and press the detonator. "But at the moment he was to press the button he forgot Paradise," one of his former cellmates recalled. "He felt a split second of fear, a slight hesitation. To bolster himself, he recited from the Koran. Refreshed and strengthened, he again began to think of Paradise. When he felt ready, he tried again. But the detonator did not function. He prayed to himself, 'Please, Allah, let me succeed.'But still it did not work, not even the third time, when he kept his finger pressed firmly on the knob. Recognizing that there was a technical problem, he got off the bus at the next stop, returned the bag to the planner, and went home." (The Israeli security services subsequently arrested M. in another attack, and he is currently in prison.) Many of the volunteers and the members of their family told stories of persecution, including beatings and torture, suffered at the hands of Israeli forces. I asked whether some of the bombers acted from feelings of personal revenge. "No," a trainer told me. "If that ,alone motivates the candidate, his martyrdom will not be acceptable to AHah. lt is a military response, not an individu,al's bitterness, that drives an operation. Honor and dignity are very important in our culture. And when we are humiliated we respond with wrath."

AI kbaliyya al istisbhadiyya, which is often mistranslated as "suicide cell"-its proper translation is "martyrdom cell is the basic building block of operations. Generally, each cell consists of a leader and two or three young men. When a candidate is placed in a cell, usually after months, if not years, of religious studies, he is assigned the lofty title of al shaheed al hayy, "the living martyr." He is also referred to as "he who is waiting for martyrdom." A young man named Ayman Juma Radi, whose self-explosion, in December, 1994, was delayed by a few days, wrote a message in his diary, in which he glumly signed himself "the deferred martyr." Each cell is tightly compartmentalized and secret. Cell members do not discuss their affiliation with their friends or family, and even if two of them know each other in normal life, they are not aware of the other's membership in the same cell. (Only the leader is known to both.) Each cell, which is dissolved after the operation has been completed, is given a name from the Koran or from Islamic history. ln most cases, the young men undergo intensified spiritual exercises, including prayers and recitations of the Koran. Usually, the trainer encourages the candidate to read six particular chapters of the Koran: Baqara, Al Imran, Anfal, Tawba, Rahman, and Asr, which feature such themes as jlhad, the birth of the nation of Islam, war, Allah's favors, and the importance of faith. Religious lectures last from two to four hours each day. The living martyr goes on lengthy fasts. He spends much of the night praying. He pays off all his debts, and asks for forgiveness for actual or perceived offenses. If a candidate is on the wanted list of the Israeli security services, he goes underground, moving from one hiding place to another. In the days before the operation, the candidate prepares a will on paper, audiocassette, or video, sometimes all three. The video testaments, which are shot against a background of the sponsoring organization's banner and slogans, show the living martyr reciting the Koran, posing with guns and bombs, exhorting his comrades to follow his example, and extolling the virtues of jihad. The wills emphasize the voluntary basis of the mission. "This is my free decision, and 1I urge all of you to follow me," one young bomber, Muhammad Abu Hashem, said in a recorded testament before blowing himself up, in 1995, in retaliation for the assassination of Fathi Shlqaql. The young man repeatedly watches the video of himself, as wen as the videos of his predecessors. "These videos encourage him to confront death, not fear it," one trainer told me. "He becomes intimately familiar with what he is about to do. Then he can greet death Eke an old friend." Just before the bomber sets out on his final journey, he performs a ritual ablution, puts on clean clothes, and tries to attend at least one communal prayer at a mosque. He says the traditional Islamic prayer that is customary before battle, and he asks Allah to forgive his sins and to bless his mission. lie puts a Koran in his left breast pocket, above the heart, and he straps the explosives around his waist or picks up a briefcase or a bag containing the bomb. The planner bids him farewell with the words "May Allah be with you, may Allah give you success so that you achieve Paradise." The would-be martyr responds, "Inshallah, we will meet in Paradise." Hours later, as he presses the detonator, he says, "Allahu akbar" "AJlah is great. All praise to Him."

The operation doesn't end with the explosion and the many deaths. Hamas and Islamic Jihad distribute copies of the martyr's audiocassette or video to the media and to local organizations as a record of their success and encouragement to other young men. His act becomes the subject of sermons in mosques, and provi 'des material for leaflets, posters, videos, demonstrations, and extensive coverage in the media. Graffiti on walls in the martyr's neighborhood praise his heroism. Aspiring martyrs perform mock reenactments of the operation, using models of exploding cars and buses. The sponsoring organization distributes cassettes of chants and songs honoring the good soldier. When a member of al-Qassam blew up himself and his victims in April, 1994, in retaliation for the massacre of Muslim worshippers in Hebron by the Israeli extremist Baruch Goldstein, he was commemorated in an anthem that ushered in a new popular genre of "revenge songs. The bomber's family and the sponsoring organization celebrate his martyrdom with festivities, as if it were a wedding. Hundreds of guests congregate at the house to offer congratulations. The hosts serve the juices and sweets that the young man specified in his win. Often, the mother wiu ululate in joy over the honor that AHah has bestowed upon her family. But there is grief, too. I asked the mother of Ribhi Kahlout, a young man in the Gaza Strip, who had blown himself up, in November, 1995, what she would have done if she had known what her son was planning to do. "I woldd have taken a cleaver, cut open my heart, and stuffed him deep inside," she said. "Then I would have sewn it up tight to keep him safe." +

Rumours of War NZ Listener 15 Dec 2001

Beyond the headline coverage of the 'war against terror' lies a parallel universe of alternative media and analysis.

BY MARK REVINGTON Stan Goff is funny, smart and eloquent. And so far to the left of George W Bush that they might be on different planets. Bush says that Osama bin Laden is an evildoer, sheltered by the Taliban, and it's the moral duty of his government to bomb Afghanistan to bits to get rid of him. Wait a second, says Goff. Cafl that a war on terrorism? From where he sits, it looks more like the Bush administration using the tragic events of September 11 as an unfortlmate catalyst in a 21st-century version of "the Great Game", the name that Rudyard Kipling gave to the 19th-century imperial powers' strategic squabbles in central Asia. Goff writes a long piece, "The So-called Evidence Is a Farce", and posts it to an online community. It spreads like a benign virus: "The most cursory glance at the verifiable facts, before, during, and after September 11, does not support the official line nor conform to the current actions of the United States Government. " just another conspiracy crackpot? What makes Gofrs point of view more interesting is his background as a US Special Forces veteran. He taught tactics at the Jungle Operations Centre in Panama, military science at West Point, and served in eight different conflict zones, from Vietnam to Somalia, over 24 years. Then, in 1994, while part of Operation Restore Democracy in Haiti, he had an epiphany, left the army, took a radical tum, and wrote a book called Hideous Dream: A Soldier's Memoir of the US Invasion of Haiti. "The army sent me to probably one too many places they shouldn't have sent me," he says from his home in North Carolina. "The pieces started falling into place." He now works as the organising director of Democracy South, a 12-state progressive political network, and sometimes as a military technical adviser on films. He's tickled pink to get a call from New Zealand. The only Kiwi he knows is actor Cliff Curtis.

"He was playing in an Arnold Schwarzenegger movie that I worked on as tech adviser here last year. Cliff is actually the chief bad guy. It's not out yet. They held it because it was so much like September 1 1. " Softly spoken, thoughtful and at pains to stress that although he has serious questions about September 11 (primarily that the precision and execution of the terrorist acts smack of far more than mere fanatical amateurism), he's not alleging a government conspiracy. "There are huge contradictions and it is important to raise those questions, but it is more important to understand the larger context." The larger context, he proposes, is oil, and Goffs is just one voice in a tapestry of scepticism surfacing everywhere, from Internet sites to the pages of the Establishment press: George W made his first niil- lion in oil, with the help of an invest:rnent from Osama bin Laden's brother; National Security Adviser Condoleeza Rice, a manager at Chevron for the past decade, has an oil tanker named after her; Vice President Dick Cheney made his fortune as CEO of Halliburton, the world's largest supplier of oilfield equipment - although he's a little guarded about his former company's clients. (That's perhaps not surprising when you consider that, as Secretary of Defence for George Bush Sr, Cheney oversaw the destruction of Iraqs oil infrastructure during the Gulf war, then, as the Financial Times revealed, oversaw $US23.8 million in sales to Iraq in 1998 and 1999. This despite insisting that it was company policy not to deal with Iraq, "even arrangements that were supposedly legal".) The Taliban entered the oil equation as the likeliest guarantors of regional stability, a prerequisite for US investment. In 1998, the Unocal oil company told a congressional committee that it wanted to build a $2.5 billion pipeline from the Caspian Basin through Afghanistan to the Pakistan coastline to serve Asian markets. In a just-released book by French intelligence analysts Charles Brisard and Guillaume Dasquie, it is claimed that the Taliban were told by US negotiators to "accept the offer of a carpet of gold or be buried under a carpet of bombs". So, the sceptics ask, did the US decide to bomb Afghanistan in retaliation for September 11, or was it a strategic manoeuvre about oil? "I think there are more than a few parallels to the Great Game," says Goff. "And it's more than just the geographical positioning now. It's this whole question of Caspian Basin oil." As Jonathan Freedland wrote recently in the Guardian, the oil question must also be asked of Russia's Vladimir Putin, so far the big winner in Afghanistan, with "the prospect of a lucrative deal to sell Russian oil to an America an)dous to wean itself off the politically unstable Gulf variety".

These are the whispers and rumours and outright accusations

in a narrative That runs parallel to the derring-do tales of "elite"

soldiers and brave marines at the enemy gates; it attempts to

penetrate the meetings, minds and secrets of elite policymakers

and military strategists. The Times of lndia, for instance, recently

published a story based on an Indian Government intelligence report

linking Pakistan intelligence service ISI) chief Lt General Mahmoud

Ahmad, with both the US State Department and Mohamed Atta the

presumed ring leader of Sept 11 hijackers. According to Chonsudovsky,

Professor of Economics at the University of Ottawa, who published

an online paper about this, the report also indicates that other

ISI officials might have had contacts with the terrorists. "Moreover,

it suggests that the September 11 attacks were not an act of 'individual

terrorism' organised by a separate al Qaeda cell, but rather they

were part of a coordinated military-intelligence operation, emanating

from Pakistan's ISI. " Was the US prepared for military action

in Afghanistan before September 11? Pakistan's former Foreign

Minister Niaz Naik says that senior American officials told him

as early as mid-July that military action against Afghanistan

would go ahead by the middle of October. US deputy defence secretary

Paul Wolfowitz is reported to have said that the US had not contemplated

sending its own troops in before September 11, but had talked

about an air campaign backing local troops. BBC's Newsnight and

the Guardian have also claimed that US intelligence agencies had

been told to "back off from investigations involving members

of the bin Laden family, the Saudi royals and possible Saudi links

to the acquisition of nuclear weapons by Pakistan. The Guardian

said that "high-placed" intelligence sources stated

that there were always constraints on investigating the Saudis,

and it got worse after the Bush administration came to power.

Those claims are supported in the Brisard and Dasquie book, which

says that Bush obstructed investigations into Taliban terrorist

activities at the behest of oil companies. The pair claim that

FBI Deputy Director John O'Neill (who died in the September 11

attacks) resigned in July in protest at Bush's interference. O'Neill

is said to have told the authors that "all the answers, and

everything needed to dismantle bin Laden's al Qaeda, can be found

in Saudi Arabia". The shadows grow longer further from the

mainstream. A publication called the Economic Intelligence Review

takes a New York Times report about the hawkish camp within the

Bush administration and comes up with "the Wolfowitz cabal",

named after Deputy Defence Paul Wolfowitz: "According to

the New York Times, which published a leak about their activities

on Oct 12 the grouping wants an immediate with Iraq, believing

that the targeting of Afghanistan, already an impoverished wasteland,

falls far short of the global war that they are hoping for. But

Iraq is just another stepping stone to turning the anti-terrorist

'war' into a full-blown 'Clash of Civilisations', where the Islamic

religion would become the 'enemy linage' in a 'new Cold War'.

" A new paranoia, too. US Attorney General John Ashcroft

has pushed through the USA Patriot Act, otherwise known as the

"Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate

Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act",

which gives sweeping new powers to US law enforcement and intelligence

agencies to spy on US citizens without any judicial checks and

balances. He faces increased congressional questioning about the

justice Departrnent's round-up of hundreds of swarthy men on immigration

charges. Ashcroft won't name those detained, saying he doesn't

want to aid al Qaeda. In fact, Goff begins to sound like the voice

of reason when he says that there is no way to protect the US

from unconventional attacks such as those of September 11. What

looks like overwhelming US public support for Operation Enduring

Freedom is "a mile wide and an inch thick", he says.

"The unanimity in Congress is unravelling at the edges. People

are beginning to sit down and make a more cool-headed assessment

of what some of this stuff means. People are beginning to understand

that we paid the Taliban salaries two

years ago. "We have a whole litter of Dr Strangeloves going

on here. I don't know who is scarier, [US Secretary of Defence]

Rumsfeld, Ashcroft or Wolfowitz. Progressives in the US are very

alarmed right now. Some are responding by waiting for all this

to pass. A lot of us are saying that is wrong. You can't look

at this as the McCarthy era all over again. This is more like

1935 in Germany. They want everyone to acquiesce. You've got to

take a stand and take a stand now and roll this back with everything

you've got."

Hubris A Lesson from Ancient Greeks Gwynne Dyer London Stratford Press Dec 15 2001

'GET them by the balls, and their hearts and minds will follow,' went the Vietnam-era adage of the professional United States' military. But the US, despite the enormous fire- power that gave it so many military victories, ultimately lost the Vietnam war. With the Taleban regime destroyed and the al Qaeda organisation deprived of its bases in Afghanistan, the hawks in the Bush administration are in full charge. Last weekend, American military officers were in Somalia meeting with warlords from the Rahanwein Resistance Army to discuss a joint attack on that country's fledgling government, and Undersecretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs Ryan Crocker was in Kurdish-controlled northern Iraq laying the groundwork for an assault on Saddam Hussein's regime. The next phase of the 'war on terrorism" may be no further away than the traditional New Year's hang-over, and the voices of doubt and dissent in Washington have almost all been stilled. 'Bombing works" is the cry, and casualty-free victories are coming to be taken for granted in the United grates, and almost anything seems possible. The ancient Greeks call this state of mind "hubris" - and expected Nemesis to follow. Elsewhere, the sense is that the US is over-extending itself, and alarm among its closest allies is growing- On December 11, for example, Britain's Chief of Defence Staff, Admiral Sir Michael Boyce, warned that the emotionally satisfying fireworks in Afghanistan had hardly affected the real level of the terrorist threat. Al Qaeda, he said, remains "a fielded, resourced, dedicated and essentially autonomous terrorist force, quite capable of atrocity on a comparable scale' to the attacks on New York and Washington on September 11. Of course it does. The attacks on New York and Washington were not planned and pre- pared in caves in Afghanistan, though bin Laden was doubtless kept informed. They were planned and prepared and in all likelihood thought up as well by autonomous cells of al Qaeda based in Europe and the US. The whole Afghan sideshow, like the forth- coming ones in Somalia, Iraq and elsewhere, will have only a marginal impact on the ability of those cells to act. Indeed, the long-term effect of such extended bombing campaigns could be to expand the Recruiting base for al Qaeda and like-minded organisations both in the Muslim world and the diaspora. As Admiral Boyce put it, the risk is that handing over Western security policy to a 'hi-tech 21st-century posse" will radicalise the entire Muslim world, and produce a global confrontation far more serious than the dramatic but strictly limited threats posed by occasional terrorist strikes. Indeed, a failure to wage a campaign for 'hearts and minds" (and he actually said those deeply unfashionable words) will probably make the terrorist threat worse too. Britain is not America's enemy. Prime Minister Tony Blair has been Washington's closest ally, donning pom-poms and tassels to cheer-lead the US war on terrorism, and the British army will both command and provide the biggest contingent for the peace-keeping force that arrives in Afghanistan to take the place of the limited US forces that have been committed on the ground within a month. (The United States doesn't do 'nation-build- ing, and it doesn't do ground warfare much any more either.) Admiral Boyce was not just saying the first thing that came into his head. Such speeches are vetted at Cabinet level, and the anxieties Boyce expressed are those that all of America's friends and allies feel as Washington, encouraged by the easy Afghan victory, plunges on to new campaigns. But nobody in the White House is listening. Three months ago, as the United States was busy rounding up support for its new war on terrorism, there was a brief pause in the Bush administration's relentless war against any treaties that might constrain American power in any way, but the unilateralist drive has now resumed with full force. The Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty is being cancelled with six months' notice, and the US will push ahead with Bush's beloved Ballistic Missile Defence, despite near-universal misgivings among friends and allies. Washington recently blocked moves to tighten the convention aimed at prohibiting the development of biological weapons. It has forced European countries to put their plans for a joint Nato-Russia council on hold for at least six months: it doesn't want its old allies and its new one to get too cozy. Even when it does make a commitment - as with President George W. Bush's recent verbal agreement with Russian President Vladimir Putin on cutting missile numbers - it doesn't want to commit the deal to writing. This combination of technological hubris and ideological triumphalism is leading the Bush administration into dangerous waters. The US is a big, rich, powerful and technologically innovative country, but it is still only 4% of the world's population. In the 60 years since the Pearl Harbour attack pulled it into World War II and made it a full-time player in global politics, it always played the alliance game because successive administrations all understood that even American power could be over-stretched. If that lesson now has to be re-learned, we are all in for a rough time.

THE REVOLT OF ISLAM When did the conflict with the West begin, and how could it end? BY BERNARD LEWIS - MAKING HISTOKY NY 19 nov 2001

President Bush and other Western Politicians have taken great pains to make it clear that the war in which we are engaged is a war against terrorism - not a war against Arabs, or, more generally, against Muslims, who are urged to join us wholesale against our common enemy. Osama bin Laden's message is the opposite. For bin Laden and those who follow him, this is a religious war, a war for Islam and against infidels, and therefore, inevitably, against the United States, the greatest power in the world of the infidels. In his pronouncements, bin Laden makes frequent references to history. One of the most dramatic was his mention, in the October 7th videotape, of the "humiliation and disgrace" that Islam has suffered for "more than eighty years." Most American - and, no doubt, European - observers of the Middle Eastern scene began an anxious search for something that had happened "more than eighty years" ago, and came up with various answers. We can be fairly sure that bin Laden's Muslim listeners-the people he was addressing picked up the allusion immediately and appreciated its significance. In 1918, the Ottoman sultanate, the last of the great Muslim empires, was finally defeated - its capital, Constantinople, occupied, its sovereign held captive, and much of its territory partitioned between the victorious British and French Empires. The Turks eventuaUy succeeded in liberating their homeland, but they did so not in the name of Islam but through a secular nationalist movement. One of their first acts, in November, 1922, was to abolish the sultanate. The Ottoman sovereign was not only a sultan, the ruler of a specific state; he was also widely recognized as the caliph, the head of all Sunni lslam, and the last in a line of such rulers that dated back to the death of the Prophet Muhammad, in 632 A.D. After a brief experiment with a separate caliph, the Turks, in March, 1924, abolished the caliphate, too. During its nearly thirteen centuries, the caliphate had gone through many vicissitudes, but it remained a potent symbol of Muslim unity, even identity, and its abolition, under the double assault of foreign imperialists and domestic modernists, was felt throughout the Muslim world. Historical allusions such as bin Laden's, which may seem abstruse to many Americans, are common among Muslims, and can be properly understood only within the context of Middle Eastern perceptions of identity and against the background of Middle Eastern history. Even the concepts of history and identity require redefinition for the Westerner trying to understand the contempora.ry Middle East. In current American usage, the phrase "that's history" is commonly used to dismiss something as unimportant, of no relevance to current concerns, and, despite an immense investment in the teaching and writing of history, the general level of historical knowledge in our society is abysmally low. The Muslim peoples, like everyone else in the world, are shaped by their history, but, unlike some others, they are keenly aware of it. In the nineteen-eighties, during the Iran-lraq war, for instance, both sides waged massive propaganda campaigns that frequently evoked events and personalities dating back as far as the seventh century. These were not detailed narratives but rapid, incomplete allusions, and yet both sides employed them in the secure knowledge that they would be understood by their target audiences - even by the large proportion of that audience that was illiterate. Middle Easterners' perception of history is nourished from the pulpit, by the schools, and by the media, and, although it may be-indeed, often is slanted and inaccurate, it is nevertheless vivid and powerfully resonant. But history of what? In the Western world, the basic unit of human organization is the nation, which is then subdivided in various ways, one of which is by religion. Muslims, however, tend to see not a nation subdivided into religious groups but a religion subdivided into nations. This is no doubt partly because most of the nation-states that make up the modern Middle East are relatively new creations, left over from the era of Anglo-French imperial domination that followed the defeat of the Ottoman Empire, and they preserve the state-building and frontier demarcations of their former imperial masters. Even their names reflect this artificiality: Iraq was a medieval province, with borders very different from those of the modem republic; Syria, Palestine, and Libya are names from classical antiquity that hadn't been used in the region for a thousand years or more before they were revived and imposed by European imperialists in the twentieth century; Algeria and Tunisia do not even exist as words in Arabic - the same name serves for the city and the country. Most remarkable of all, there is no word in the Arabic language for Arabia, and modern Saudi Arabia is spoken of instead as "the Saudi Arab kingdom" or "the peninsula of the Arabs," depending on the context. This is not because Arabic is a poor language - quite the reverse is true - but because the Arabs simply did not think in terms of combined ethnic and territorial identity. Indeed, the caliph Omar, the second in succession after the Prophet Muhammad, is quoted as saying to the Arabs, "Learn your genealogies, and do not be like the local peasants who, when they are asked who they are, reply:' l am from such-and-such a place."' In the early centuries of the Muslim era, the Islamic community was one state under one ruler. Even after that community split up into many states, the ideal of a single Islamic polity persisted. The states were almost all dynastic, with shifting frontiers, and it is surely significant that, in the immensely rich historiography of the Islamic world in Arabic, Persian, and Turkish, there are histories of dynasties, of cities, and, primarily, of the Islamic state and community, but no histories of Arabia, Persia, or Turkey. Both Arabs and Turks produced a vast literature describing their struggles against Christian Europe, from the first Arab incursions in the eighth century to the final Turkish retreat in the twentieth. But until the modem period, when European concepts and categories became dominant, Islamic commentators almost always referred to their opponents not in temtorial or ethnic terms but simply as infidels (kafir). They never referred to their own side as Arab or Turkish; they identified themselves as Muslims. This perspective helps to explain, among other things, Pakistan's concem for the Taliban in Afghanistan. The name Pakistan, a twentieth century invention, designates a country defined entirely by its Islamic religion. ln every other respect, the country and people of Pakistan are- as they have been for miflennia - part of India. An Afghanistan defined by its Islamic identity would be a natural ally, even a satellite, of Pakistan. An Afghanistan defined by ethnic nationality, on the other hand, could be a dangerous neighbor, advancing irredentist claims on the Pashto-speaking areas of northwestern Pakistan and perhaps even identifyng itself with India.

lI-THE HOUSE OF WAR

In the course of human history, many civilizations have risen and fallen China, India, Greece, Rome, and, before them, the ancient civilizations of the Middle East. During the centuries that in European history arc called medieval, the most advanced civilization in the world was undoubtedly that of Islam. Islam may have been equalledor even, in some ways, surpassed-by India and China, but both of those civilizations remained essentially limited to one region and to one ethnic group, and their impact on the rest of the world was correspondingly restricted. The civilization of Islam, on the other hand, was ecumenical in its outlook, and explicitly so in its aspirations. One of the basic tasks bequeathed to Muslims by the Prophet was jihad. This word, which literally means "striving," was usually cited in the Koranic phrase "striving in the path of God" and was interpreted to mean armed struggle for the defense or advancement of Muslim power. In principle, the world was divided into two houses: the House of Islam, in which a Muslim government ruled and Muslim law prevailed, and the House of War, the rest of the world, still inhabited and, more important, ruled by infidels. Between the two, there was to be a perpetual state of war until the entire world either embraced Islam or submitted to the rule of the Muslim state. From an early date, Muslims knew that there were certain differences among the peoples of the House of War. Most of them were simply polytheists and idolaters, who represented no serious threat to Islam and were likely prospects for conversion. The major exception was the Christians, whom Muslims recognized as having a religion of the same kind as their own, and therefore as their primary rival in the struggle for world domination - or, as they would have put it, world enlightenment. It is surely significant that the Koranic and other inscriptions on the Dome of the Rock, one of the earliest Muslim religious shrines outside Arabia, built in Jerusalem between 691 and 692 A.D., include a number of directly anti-Christian polemics: "Praise be to God, who begets no son, and has no partner," and "He is God, one, eternal. He does not beget, nor is he begotten, and he has no peer." For the early Muslims, the leader of Christendom, the Christian equivalent of the Muslim caliph, was the Byzantine emperor in Constantinople. Later, his place was taken by the Holy Roman Emperor in Vienna, and his in turn by the new rulers of the West. Each of these, in his time, was the principal adversary of the jlhad. ln practice, of course, the application of jihad wasn't always rigorous or violent. The canonically obligatory state of war could be interrupted by what were legally defined as "truces," but these differed little from the so-called peace treaties the warring European powers signed with one another. Such truces were made by the Prophet with his pagan enemies, and they became the basis of what one might call Islamic international law. In the lands under Muslim rule, Islamic law required that Jews and Christians be allowed to practice their religions and run their own affairs, subject to certain disabilities, the most important being a poll tax that they were required to pay. In modern parlance, jews and Christians in the classical Islamic state were what we would call second-class citizens, but second-class citizenship, established by law and the Koran and recognized by public opinion, was far better than the total lack of citizenship that was the fate of non-Christians and even of some deviant Christians in the West. The jihad also did not prevent Muslim governments from occasionally seeking Christian allies against Muslim rivals - even during the Crusades, when Christians set up four principalities in the Syro-Palestinian area. The great twelfth-century Muslim leader Saladin, for instance, entered into an agreement with the Crusader king of Jerusalem, to keep the peace for their mutual convenience. Under the medieval caliphate, and again under the Persian and Turkish dynasties, the empire of Islam was the richest, most powerful, most creative, most enlightened region in the world, and for most of the Middle Ages Christendom was on the defensive. ln the fifteenth century, the Christian counterattack expanded. The Tatars were expelled from Russia, and the Moors from Spain. But in southeastern Europe, where the Ottoman sultan confronted first the Byzantine and then the Holy Roman Emperor, Muslim power prevailed, and these setbacks were seen as minor and peripheral. As late as the seventeenth century, Turkish pashas still ruled in Budapest and Belgrade, Turkish armies were besieging Vienna, and Barbary lands as distant as corsairs were raiding the British Isles and, on one occasion, in 1627, even Iceland.

Then came the great change. The second Turkish siege of Vienna, in 1683, ended in total failure followed by headlong retreat - an entirely new experience for the Ottoman armies. A contemporary Turkish historian, Silihdar Mehmet Aga, described the disaster with commendable frankness: "This was a calamitous defeat, so great that there has been none like it since the first appearance of the Ottoman state." This defeat, suffered by what was then the major miliitary power of the Muslim world, gave nse to a new debate, which in a sense has been going on ever since. The argument began among the Ottoman military and political elite as a discussion of two questions: Why had the once victorious Ottoman armies been vanquished by the despised Christian enemy? And how could they restore the previous situation? There was good reason for concern. Defeat followed defeat, and Christian European forces, having liberated their own lands, pursued their former invaders whence they had come, the Russians moving into North and Central Asia, the Portuguese into Africa and around Africa to South and Southeast Asia. Even small European powers such as Holland and Portugal were able to build vast empires in the East and to establish a dominant role in trade. For most historians, Middle Eastern and Western alike, the conventional beginning of modern history in the Middle East dates from 1798, when the French Revolution, in the person of Napoleon Bonaparte, landed in Egypt. Within a remarkably short time, General Bonaparte and his small expeditionary force were able to conquer, occupy, and rule the country. There had been, before this, attacks, retreats, and losses of territory on the remote frontiers, where the Turks and the Persians faced Austria and Russia. But for a small Western force to invade one of the heartlands of Islam was a profound shock. The departure of the French was, in a sense, an even greater shock. They were forced to leave Egypt not by the Egyptians, nor by their suzerains the Turks, but by a small squadron of the British Royal Navy, commanded by a young admiral named Horatio Nelson. This was the second bitter lesson the Muslims had to learn: not only could a Western power arrive, invade, and at will but only another Western power could get it out. By the early twentieth century though a precarious independence was retained by Turkey and Iran and by some remoter countries like Afghanistan, which at that time did not seem worth the trouble of invading - almost the entire Muslim world had been incorporated into the four European empires of Britain, France, Russia, and the Netherlands. Middle Eastern governments and factions were forced to learn how to play these mighty rivals off against one another. For a time, they played the game with some success. Since the Western allies - Britain and France and then the United States - effectively dominated the region, Middle Eastern resisters naturally looked to those allies' enemies for support. In the Second World War, they turned to Germany; in the Cold War, to the Soviet Union. And then came the collapse of the Soviet Um'on, which left the United States as the sole world superpower. The era of Middle Eastern history that had been inaugurated by Napoleon and Nelson was ended by Gorbachev and the elder George Bush. At first, it seemed that the era of imperial rivalry had ended with the withdrawal of both competitors: the Soviet Union couldn't play the imperial role, and the United States wouldn't. But most Middle Easterners didn't see it that way. For them, this was simply a new phase in the old imperial game, with America as the latest in a succession of Western imperial overlords, except that this overlord had no rival - no Hitler or Stalin whom they could use either to damage or to influence the West. In the absence of such a patron, Middle Easterners found themselves obliged to mobilize their own force of resistance. Al Qaeda - its leaders, its sponsors, its financiers - is one such force.

Ill-"THE GREAT SATAN" Americas new role - and middle East's perception of it - was vividly illustrated by an incident in Pakistan in 1979. On November 20th, a band of a thousand Muslim religious radicals seized the Great Mosque in Mecca and held it for a time against the Saudi security forces. Their declared aim was to "purify Islad' and liberate the holy land of Arabia from the royal "clique of infidels" and the corrupt religious leaders who supported them. Their leader, in speeches played from loudspeakers, denounced Westerners as the destroyers of funda mental Islamic values and the Saudi goverriment as their accomplices. He called for a return to the old Islamic traditions of justice and equality." After some hard fighting, the rebels were suppressed. Their leader was executed on January 9, 1980, along with sixty-two of his followers, among them Egyptians, Kuwaitis, Yemenis, and citizens of other Arab countries.

MeanwhUe, a demonstration in support of the rebels took place in the Pakistani capital, Islamabad. A rumor had circulated - endorsed by Ayatollah Khomeini, who was then in the process of establishing himself as the revolutionary leader in Iran - that American troops had been involved in the clashes in Mecca. The American Embassy was attacked by a crowd of Muslim demonstrators, and two Americans and two Pakistani employees were killed. Why had Khomeini stood by a report that was not only false but wildly improbable? These events took place within the context of the Iranian revolution of 1979. On November 4th, the United States Embassy in Teheran had been seized, and fifty-two Americans were taken hostage; those hostages were then held for four hundred and forty-four days, until their release on January 20, 1981. The motives for this, baffling to many at the time, have become clearer since, thanks to subsequent statements and revelations from the hostage-takers and others. It is now apparent that the hostage crisis occurred not because relations between Iran and the United States were deteriorating but because they were improving. In the fall of 1979, the retatively moderate Iranian Prime Minister, Mehdi Bazargan, had arranged to meet va'th the American national-security adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski, under the aegis of the Algerian government. The two men met on November 1st, and were reported to have been photographed shaking hands. There seemed to be a real possibility - in the eyes of the radicals, a real danger - that there might be some accommodafion between the two countries. Protesters seized the Embassy and took the American diplomats hostage in order to destroy any hope of further dialogue. For Khomeini, the United States was the Great Satan," the principal adversary against whom he had to wage his holy war for Islam. Amen'ca was by then perceived as the leader of what we like to call "the free world." Then, as in the past, this world of unbelievers was seen as the only serious force rivalling and preventing the divinely ordained spread and triumph of Islam. But American observers, reluctant to recognize the historical quality of the hostility, sought other reasons for the anti-American sentiment that had been intensifying in the Islamic world for some time. One explanation, which was widely accepted, particularly in American foreign-policy circles, was that America's image had been tarnished by its wartime and continuing alliance with the former colonial powers of Europe. In their countrys defense, some American commentators pointed out that, unlike the Western European imperialists, America had itself been a victim of colonialism; the United States was the first country to win freedom from British rule. But the hope that the Middle Eastern subjects of the former British and French Empires would accept the American Revolution as a model for their own anti-imperialist struggle rested on a basic fallacy that Arab writers were quick to point out. The American Revolution was fought not by Native American nationalists but by British settlers, and, far from being a victory against colonialism, it represented colonialists ultimate triumph the English in North America succeeded in colonizing the land so thoroughly that they no longer needed the support of the mother country. It is hardly surprising that former colonial subjects in the Middle East would see America as being tainted by the same kind of imperialism as Westem Europe. But Middle Eastem resentment of imperial powers has not always been consistent. The Soviet Union, which extended the imperial conquests of the tsars of Russia, ruled with no Eght hand over tens of millions of Muslim subjects in Central Asian states and in the Caucasus; had it not been for American opposition and the Cold War, the Arab world might well have shared the fate of Poland and Hungary, or, more probably, that of Uzbekistan. And yet the Soviet Union suffered no simuar backlash of anger and hatred from the Arab community. Even the Russian invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 - a clear case of imperialist aggression, conquest, and domination - triggered only a muted response in the Islamic world. The P.L.O. observer at the United Nations defended the invasion, and the Organization of the Islamic Conference did little to protest it. South Yemen and Syria boycotted a meeting held to discuss the issue, Libya delivered an attack on the United States, and the P.L.O. representative abstained from voting and submitted his reservations in writing. Ironically, it was the United States, in the end, that was left to orchestrate an Islamic response to Soviet imperialism in Afghanistan.

As the Western European empires faded, Middle Eastern anti-Americanism was attributed more and more to another cause: American support for Israel, first in its conflict with the Palestinian Arabs, then in its conflict with the nel,ghboring Arab states and the larger Islamic world. There is certainly support for this hypothesis in Arab statements on the subject. But there are incongruities, too. In the nineteen-thirties, Nazi Germany's policies were the main cause of Jewish migration to Palestine, then a British mandate, and the consequent reinforcement of the Jewish community there. The Nazis not ordy permitted this migration; they facilitated it until the outbreak of the war, while the British, in the somewhat forlorn hope of winning Arab good will, imposed and enforced restrictions. Nevertheless, the Palestinian leadership of the time, and many other Arab leaders, supported the Germans, who sent the jews to Palestine, rather than the British, who tried to keep them out. The same kind of discrepancy can be seen in the events leading to and following the establishment of the State of Israel, in 1948. The Soviet Union played a significant role in procuring the majority by which the General Assembly of the United Nations voted to estabesh a Jewish state in Palestine, and then gave Israel immediate de-jure recognition. The United States, however, gave only de-facto recognition. More important, the American government maintained a partial arms embargo on Israel, while Czechoslovakia, at Moscow's direction, immediately sent a supply of weaponry, which enabled the new state to survive the attempts to strangle it at birth. As late as the war of 1967, Israel still rehlied for its arms on European, mainly French, suppliers, not on the United States.

The Soviet Union had been one of Israel's biggest supporters. Yet, when Egypt announced an arms deal with Russia, in September of 1955, there was an overwhelmingly enthusiastic response in the Arab press. The Chambers of Deputies in Syria, Lebanon, and jordan met immediately and voted resolutions of congratulation to President Nasser; even Nun Said, the pro-Western ruler of Iraq, felt obliged to congratulate his Egyptian colleague - this despite the fact that the Arabs had no special love of Russia, nor did Muslims in the Arab world or elsewhere wish to invite either Communist ideology or Soviet power to their lands. What delighted them was that they saw the arms deal - no doubt correctly - as a slap in the face for the West. The slap, and the agitated Western response, reinforced the mood of hatred and spite toward the West and encouraged its exponents. It also encouraged the United States to look more favorably on Israel, now seen as a reliable and potentially useful ally in a largely hostile region. Today, it is often forgotten that the strategic relationship between the United States and Israel was a consequence, not a cause, of Soviet penetration. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is only one of many struggles between the Islamic and non-Islamic worlds - on a list that includes Nigeria, Sudan, Bosnia, Kosovo, Macedonia, Chechnya, Sinkiang, Kashmir, and Mindanao - but it has attracted far more attention than any of the others. There are several reasons for this. First, since Israel is a democracy and an open society, it is much easier to report - and misreport - what is going on. Second, Jews are involved, and this can usually secure the attention of those who, for one reason or another, are for or against them. Third, and most important, resentment of lsrael is the only grievance that can be freely and safely expressed in those Muslim countries where the media are either wholly owned or strictly overseen by the government. Indeed, Israel serves as a useful stand-in for complaints about the economic privation and political repression under which most Muslim people live, and as a way of deflecting the resulting anger.

IV-DOUBLE STANDARDS

This raises another issue. Increasingly in recent decades, Middle Easterners have articulated a new grievance against American policy: not American complicity with imperialism or with Zionism but something nearer home and more immediate - American complicity with the corrupt tyrants who rule over them. For obvious reasons, this particular complaint does not often appear in public discourse. Middle Eastern governments, such as those of Iraq, Syria, and the Palestine Authority, have developed great skill in controlling their own media and manipulating those of Western countries. Nor, for equally obvious reasons, is it raised in diplomatic negotiation. But it is discussed, with increasing anguish and urgency, in private conversations with listeners who can be trusted, and recently even in public. (Interestingly, the Iranian revolution of 1979 was one time when this resentment was expressed openly. The Shah was accused of supporting America, but America was also attacked for imposing an impious and tyrannical leader as its puppet.) Almost the entire Muslim world is affected by poverty and tyranny. Both of these problems are attributed, especially by those with an interest in diverting attention from themselves, to America the first to American economic dominance and exploitation, now thinly disguised as "globalization'; the second to America's support for the many so-called Muslim tyrants who serve its purposes. Globalization has become a major theme in the Arab media, and it is almost always raised in connection with American economic penetration. The increasingly wretched economic situation in most of the Muslim world, relative not only to the West but also to the tiger economies of East Asia, fuels these frustrations. American paramountly, as Middle Easterners see it, indicates where to direct the blame and the resulting hostility. There is some justice in one charge that is frequently levelled against the United States: Middle Easterners increasingly complain that the United States judges them by different and lower standards than it does Europeans and Americans, both in what is expected of them and in what they may expect - in terms of their financial wellbeing and their political freedom. They assert that Western spokesmen repeatedly overlook or even defend actions and support rulers that they would not tolerate in their own countries. As many Middle Easterners see it, the Western and American governments' basic position is: "We don't care what you do to your own people at home, so long as you are cooperative in meeting our needs and protecting our interests." The most dramatic example of this form of racial and cultural arrogance was what Iraqis and others see as the betrayal of 1991, when the United States called on the Iraqi people to revolt against Saddam Hussein. The rebels of northern and southern Iraq did so, and the United States forces watched while Saddam, using the helicopters that the ceasefire agreement had allowed him to retain, bloodily suppressed them, group by group. The reasoning behind this action - or, rather, inaction - is not difficult to see. Certainly, the victorious Gulf War coalition wanted a change of government in lraq, but they had hoped for a coup d'etat, not a revolution. They saw a genuine popular uprising as dangerous-it could lead to uncertainty or even anarchy in the region. A coup would be more predictable and could achieve the desired result - the replacement of Saddam Hussein by another, more amenable tyrant, who could take his place among America's so-called allies in the coalition. The United States' abandonment of Afghanistan after the departure of the Soviets was understood in much the same way as its abandonment of the Iraqi rebels. Another example of this double standard occurred in the Syrian city of Hama and in refiigee camps in Sabra and Shatila. The troubles in Hama began with an uprising headed by the radical group the Muslim Brothers in 1982. The government responded swiftly. Troops were sent, supported by armor, artillery, and aircraft, and within a very short time they had reduced a large part of the city to rubble. The number killed was estimated, by Amnesty International, at somewhere between ten thousand and twenty-five thousand. The action, which was ordered and supervised by the Syrian President, Hafiz al-Assad, attracted little attention at the time, and did not prevent the United States from subsequently courting Assad, who received a long succession of visits from American Secretaries of State James Baker, Warren Christopher, and Madeleine Albright, and even from President Clinton. It is hardly likely that Americans would have been so eager to propitiate a ruler who had perpetrated such crimes on Westem soil, with Western victims. The massacre of seven hundred to eight hundred Palestinian refiigees in Sabra and Shatila that same year was carried out by Lebanese militiamen, led by a Lebanese commander who subsequently became a minister in the Syrian-sponsored Lebanese government, and it was seen as a reprisal for the assassination of the Lebanese President Bashir Gemayyel. Ariel Sharon, who at the time commanded the Israeli forces in Lebanon, was reprimanded by an Israeli commission of inquiry for not having foreseen and prevented the massacre, and was forced to resign from his position as Minister of Defense. It is understandable that the Palestinians and other Arabs should lay sole blame for the massacre on Sharon. What is puzzling is that Europeans and Americans should do the same. Some even wanted to try Sharon for crimes against humanity before a tribunal in Europe. No such suggestion was made regarding either Saddam Hussein or Hafiz al-Assad, who slaughtered tens of thousands of their compatriots. It is easy to understand the bitterness of those who see the implication here. It was as if the militia who had carried out the deed were animals, not accountable by the same human standards as the Israelis. Thanks to modern communications, the people of the Middle East are increasingly aware of the deep and widening gulf between the opportunities of the free world outside their borders and the appalling privation and repression within them. The resulting anger is naturally directed first against their rulers, and then against those whom they see as keeping those rulers in power for selfish reasons. It is surely significant that most of the terrorists who have been identified in the September 11th attacks on New York and Washington come fron Saudi Arabla and Egypt - that is, from countn'es whose rulers are deemed friendly to the United States.

V A FAILURE OF MODERNITY